Kafka Unfiltered Series: The Hidden Challenges of Running Amazon MSK at Scale

Amazon MSK simplified Kafka on AWS, but at scale, networking, cost, access, and governance get complex.

All Hail MSK

When Amazon MSK was introduced in 2018, it was a pivotal moment for Kafka in the cloud. Until then, teams running Kafka on AWS were largely responsible for everything themselves: broker provisioning, ZooKeeper management, patching, scaling, monitoring, and upgrades. MSK promised to remove much of that operational burden while keeping Kafka “close to the metal” inside customers’ own VPCs, unlike fully abstracted SaaS offerings.

Since then, MSK has become one of the most commonly used Kafka offerings in the market. It underpins event-driven systems, data platforms, IoT pipelines, and real-time applications across industries. For organizations already deeply invested in AWS, MSK often becomes the obvious choice. It fits neatly into existing security models, integrates with IAM, behaves predictably from a networking perspective, and avoids introducing yet another external vendor into the stack.

Over time, however, many teams discover that managed Kafka ≠ simple Kafka. As MSK deployments grow and move beyond small, internal use cases, the nature of the complexity shifts, and the challenges that show up are rarely generic Kafka issues. They are shaped by MSK’s design decisions, AWS’s networking model, and, crucially, by how Kafka is accessed and exposed as it evolves from an internal system into a shared platform. This is where many organizations begin to rethink direct broker access and introduce a dedicated Kafka access layer to regain control, consistency, and architectural flexibility.

The Challenges of MSK

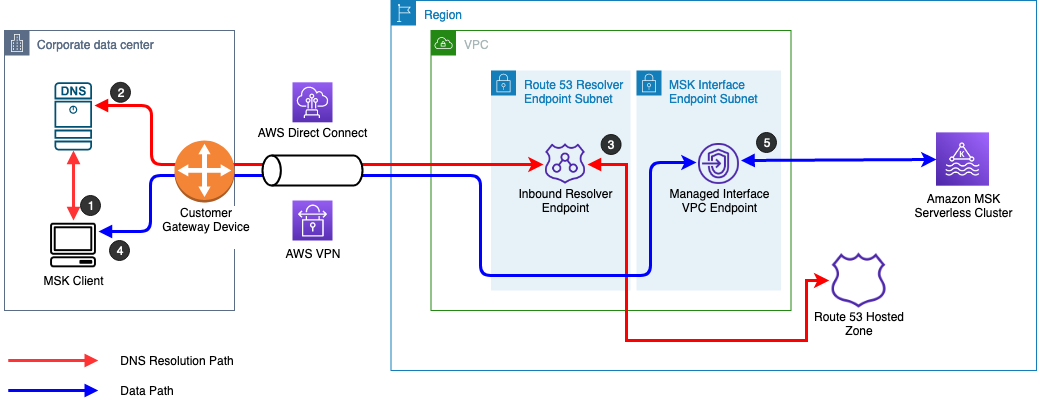

Amazon MSK is fundamentally a VPC-native service. This design choice aligns well with AWS’s security-first philosophy, but it has important consequences. Kafka clusters live entirely within private subnets, accessible only via AWS networking constructs. As long as producers and consumers remain within the same VPC (or at least within carefully peered VPCs) this model works smoothly. The moment Kafka needs to be accessed by external partners, SaaS platforms, mobile or web clients, or workloads running in other regions or accounts, the architecture becomes more complex.

At that point, teams find themselves stitching together VPC peering, Transit Gateways, PrivateLink endpoints, VPNs, DNS indirection, and TLS termination layers. Kafka itself remains unchanged, but the data plane becomes deeply entangled with AWS networking mechanics. What often begins as a one-off connectivity requirement gradually turns into a permanent part of the Kafka architecture, one that must be operated, secured, and evolved alongside the cluster itself.

Cost behavior introduces another AWS-specific dimension. Kafka generates significant east–west traffic by design, particularly through replication, consumer fetches, rebalancing, and metadata exchange. In MSK, brokers are spread across Availability Zones for resilience, but AWS charges for cross-AZ network traffic. Unless client placement, rack awareness, and consumption patterns are carefully aligned, cross-zone traffic can quietly accumulate. These costs rarely surface during early adoption and often appear only once Kafka has become a shared, multi-team platform. By that stage, traffic patterns are difficult to change without broader architectural intervention.

Authentication and authorization add further nuance. MSK supports multiple deployment modes, and they don’t all behave the same way. IAM-based authentication is appealing for AWS-native applications, but it can introduce friction for Kafka clients and tools that assume more traditional SASL or mTLS setups. Non-Java clients, legacy systems, and third-party platforms often require additional adaptation. In practice, this can mean bending client behavior to match MSK’s constraints, rather than Kafka’s more open interoperability model.

Scaling dynamics also feel different in MSK. In self-managed Kafka, limits tend to be operational: disk, CPU, network bandwidth, or controller performance. In MSK, many limits are enforced as service quotas. Connection counts, throughput ceilings, and IAM-related limits can become hard boundaries that are not easily bypassed through tuning alone. These constraints are well documented but are rarely encountered during early adoption. They surface later, when Kafka usage grows organically across teams and applications, at which point architectural flexibility has already narrowed.

Upgrades and lifecycle management introduce another layer of complexity. While MSK supports in-place Kafka version upgrades in many scenarios, not all transitions are treated equally. The industry-wide move from ZooKeeper-based Kafka to KRaft-based Kafka is a clear example. In MSK, this transition requires provisioning a new cluster and migrating workloads rather than upgrading in place. That turns what might appear to be an infrastructure upgrade into a full migration exercise, involving parallel clusters, topic replication, client coordination, and carefully managed cutovers. The managed nature of MSK simplifies some steps but removes others, leaving teams with fewer levers to fine-tune the process.

Operational control is also subtly different. AWS owns patching, maintenance behavior, and broker restarts. This is generally beneficial, but it shifts responsibility upward into application and client design. Teams must assume that brokers will be restarted, sometimes outside of perfectly aligned business windows, and that resilience must be built into consumers and producers from day one. MSK enforces Kafka best practices implicitly through infrastructure behavior rather than explicitly through policy or tooling.

Finally, while MSK provides Kafka brokers, it does not provide a complete Kafka platform. Core concerns such as schema governance, access control models, multi-tenancy, client abstraction, external exposure, and developer self-service remain firmly in the customer’s domain. AWS offers individual building blocks — managed connectors, schema registries, IAM integration — but the responsibility for assembling these into a cohesive, operable platform rests with the data platform team. As Kafka adoption spreads across the organization, this “last mile” work often becomes the dominant source of complexity.

From Broker-Centric Access to a Kafka Access Layer

In early-stage Amazon MSK deployments, Kafka clients typically connect directly to brokers inside the VPC. Application teams authenticate to MSK, discover broker endpoints through DNS, and interact with Kafka as a low-level infrastructure service. This model works well when Kafka is consumed by a small number of internal applications with tightly controlled networking boundaries. Operational responsibility remains limited, and architectural decisions feel straightforward.

As Kafka adoption expands, however, this broker-centric model begins to show strain. More teams want access. Some clients live in other AWS accounts or regions. Others are external partners, SaaS platforms, or edge-facing applications. Each new access pattern introduces additional networking constructs, authentication exceptions, and operational risk. Clients become increasingly aware of broker topology, security configuration, and lifecycle events. Over time, Kafka brokers stop being an internal detail and become a shared integration surface—one they were never designed to be.

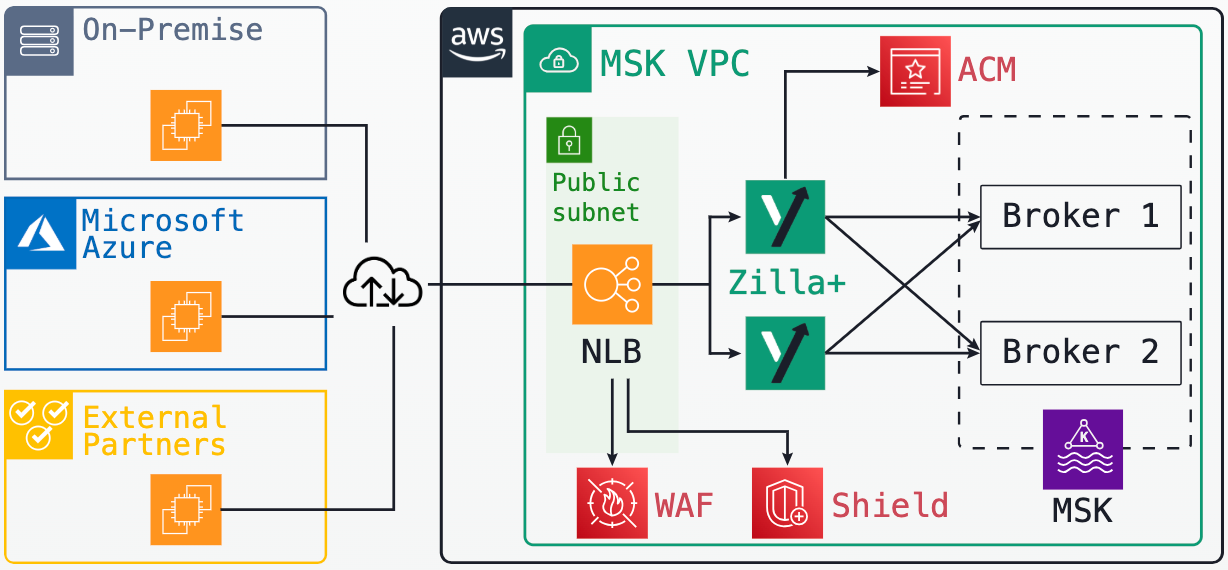

This is the point at which many organizations introduce a dedicated Kafka access layer in front of Amazon MSK. Instead of exposing brokers directly, all client traffic flows through a Kafka-native proxy or gateway deployed at the edge of the VPC. The MSK cluster remains private and stable, while the access layer becomes the controlled interface through which Kafka is consumed.

Architecturally, this shift creates a clean separation of concerns. Brokers focus on durability, replication, and throughput. Clients interact with a stable, well-defined endpoint that can handle authentication, authorization, protocol adaptation, traffic shaping, and validation independently of the cluster. Changes to broker topology, scaling events, upgrades, or even migrations can occur without forcing coordinated changes across every consuming application.

For data platform teams, this pattern provides a natural control point. It becomes possible to standardize how Kafka is exposed across teams, enforce governance consistently, and support multiple client types without fragmenting the underlying cluster. Kafka evolves from a shared infrastructure dependency into a managed data interface, one that can expand in scope without becoming more fragile.

Conclusion

Amazon MSK has succeeded because it solves a very real problem: running Kafka reliably inside AWS without running Kafka yourself. For many teams, that alone is a major win. But as Kafka evolves from an internal infrastructure component into a shared data backbone, the center of gravity shifts. The hardest problems are no longer about brokers and disks, but about access, governance, cost control, and how tightly clients are coupled to the underlying cluster.

For teams running MSK at scale, this often leads to a structural realization: direct broker access does not scale organizationally in the same way it scales technically. Introducing a dedicated Kafka access layer allows teams to preserve the operational simplicity of managed Kafka while creating a stable, governable interface for a growing and increasingly diverse set of consumers. Clients and brokers can then evolve independently, reducing risk as Kafka becomes more central to the business.

Understanding these MSK-specific trade-offs early allows teams to design Kafka platforms that scale not just in throughput, but in ownership, reach, and longevity, without being constrained by the very service that made Kafka easy to adopt in the first place.

Let’s Get Started!

Reach out for a free trial license or request a demo with one of our data management experts.